The Challenge of DEI, CRT, Justice, and the Jewish Community

And why everyone is either freaking out or not at all.

Hey everyone, something a little different today.

First, a note that I think I sent last week’s post to paying subscribers only, which was a mistake — The Cholent is for everyone! It’s a fun one and I hope you enjoy it.

For months now I have been studying the racial equity/diversity, equity, inclusion/critical race theory conversations from left, center, and right, both within and outside Jewish organizations and social media bubbles and Substacks and books and articles and conversations and podcasts and so on. In this part one of two (or more?) articles, I am going to outline the issues I wrestle with and why I think our community organizations should be thoughtful about what I call “new social justice.”

This is somewhat of a follow up to my earlier post, Is the Left Going to Lose the Jews? I want to be clear that I have no intention of throwing any of our local organizations under the bus. They all do great work and deserve support.

—Emily

After George Floyd’s death last May, the United States went through a national convulsion. Almost overnight, workplaces, governments, and organizations around the country joined a national call to action to address systemic racism and violence. Jewish communities around the country heeded this call, too. In Seattle, the newly formed Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC), a branch of the Federation that deals with legislative and policy issues, took up a racial equity statement as its first initiative. Synagogues are holding book groups and conversations around whiteness, and recently, the PNW ADL launched a webinar series to explain and defend critical race theory.

For some in the Jewish community, this is a welcome and necessary step toward full American participation and ally-ship with under-served and marginalized peoples. It’s picking up the thread of connection with the African American community, which frayed after the civil rights movement. It’s a full realization of the Torah’s mandate to pursue justice and the cultural value of tikkun olam. For others (and sometimes the same people at the same time), it conjures anxiety: Jews are both white and not white, victims of an exclusive America and benefactors of its blessings, allies in the civil rights era and alienated from the Black community. (Let’s not forget: Jewish guilt was a stereotype way before any of the current discussion.)

We must be committed to full equality and opposed to discrimination. We always have been, and we should be proud of the work we’ve done to help and continue to help so many disenfranchised Americans. At the same time, the new social justice is speeding down a track that does not fully allow for questions or alternative paths.

This leaves our community organizations in a tough position. If the choice is between anti-racism and racism, obviously we want to choose the former. But this work comes with highly loaded binaries and activist agendas that may be more harmful than helpful.

*

Diversity is an accepted good, an idea that emerged as the best bet for universities, companies, and organizations to level the playing field among minorities and women, and particularly for Black Americans in the form of affirmative action. Since the 1960s, the value and practice of diversity has both evolved and stayed the same. On the one hand, American institutions have come a long way in making themselves more colorful and less exclusively male. On the other, it’s unclear if diversity trainings have actually helped the process, or created backlash, or are ultimately just irrelevant — especially in cases where company data doesn’t bear out significant changes about the people who make it to the C-suite.

Since last summer, DEI trainers have been flooded with requests. The DEI industry is worth at least $8 billion. (DEI is a pretty big topic with a long and interesting history, and I’m not going to focus on equity and inclusion right now, but new social justice sort of balls them all up together.) While many trainings might focus more on sensitivity, the new diversity training era is bound up with new social justice thinking and terminology, very much informed by Robin DiAngelo’s runaway bestseller White Fragility and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Anti-Racist. These works present new ideas about what racism is and how it operates in our society, which is both catching people off guard and attracting adherents to a quasi-religious experience.

DiAngelo’s trainings are particularly known for their emphasis on white guilt, with critics of her approach accused of fragility and caught in an unfalsifiable loop. (You’re racist -> I’m not racist -> that’s because you’re racist.) DiAngelo’s work may be the most famous and widely read, but many other books, worksheets, charts, and exercises corroborate her approach. Exhibit A: A chart that helps white people grow from a caterpillar state of naïve colorblindness, through the chrysalis of white guilt, into a beautiful, but vaguely defined, “anti-racist” butterfly. This process requires individuals to “disintegrate” and “reintegrate” until they come away with “autonomy” where one can be “willing to step in the way of racism when possible, engage in protests.”

Not only does anti-racism require a level of religious adherence, the entire conversion process is essentially Christian, which reveals how deeply we are embedded in Christian culture and how closely the new social justice resembles a Great Awakening. One starts in a fallen state, born with sin. After realizing this culpability in evil, one must confess, do penance, do works to achieve salvation. Salvation is not a guarantee, however; it’s so easy to slip back into sin. You must continue to do the work. (Some theologians have gone so far as to compare Michael Brown Jr. with Christ, in fact. Chicago Theological Seminary president Stephen J. Ray said, “Michael Brown Jr. is and will be our shining Black Prince for from his death God has brought Life to us all and in his gaze we are enveloped in its power.” “If ‘Black Lives Matters’ is a word, then Ferguson is a word made flesh,” said Rev. Osagyefo Sekou of the Fellowship Reconciliation.)

At the same time, it’s good for people who benefit from so-called white privilege to recognize the ease of their life, from being able to choose a “good” neighborhood to never arousing the suspicion of the police and never even having to think about that when leaving the house every day of your life. Yet that recognition, and supporting objectives on a policy level to change that, are different from promoting the idea that America is wholly white supremacist and there is little we can do about it without going through a sort of 12-step program.

“White supremacy is in the air we breathe.” You have probably heard this by now. It’s a jarring concept even for many non-white Americans who have experienced racism and who believe systemic racism to be a problem. It doesn’t mean we are all de facto members of Aryan Nation (though the implication is there), but rather that “whiteness” is an insidious conspiracy, a moving target in a rigged game always on the ready to exclude certain people for their inability to adopt “white” values. Tema Okun’s primer on White Supremacy Culture, which echoes Judith Katz’s 1990 chart about “aspects and assumptions of white culture” — which influenced the Smithsonian’s guidelines for talking about race — outlines which traits of American life are actually white supremacist (“sense of urgency, timeliness, perfectionism, defen — stop it! — defensiveness).

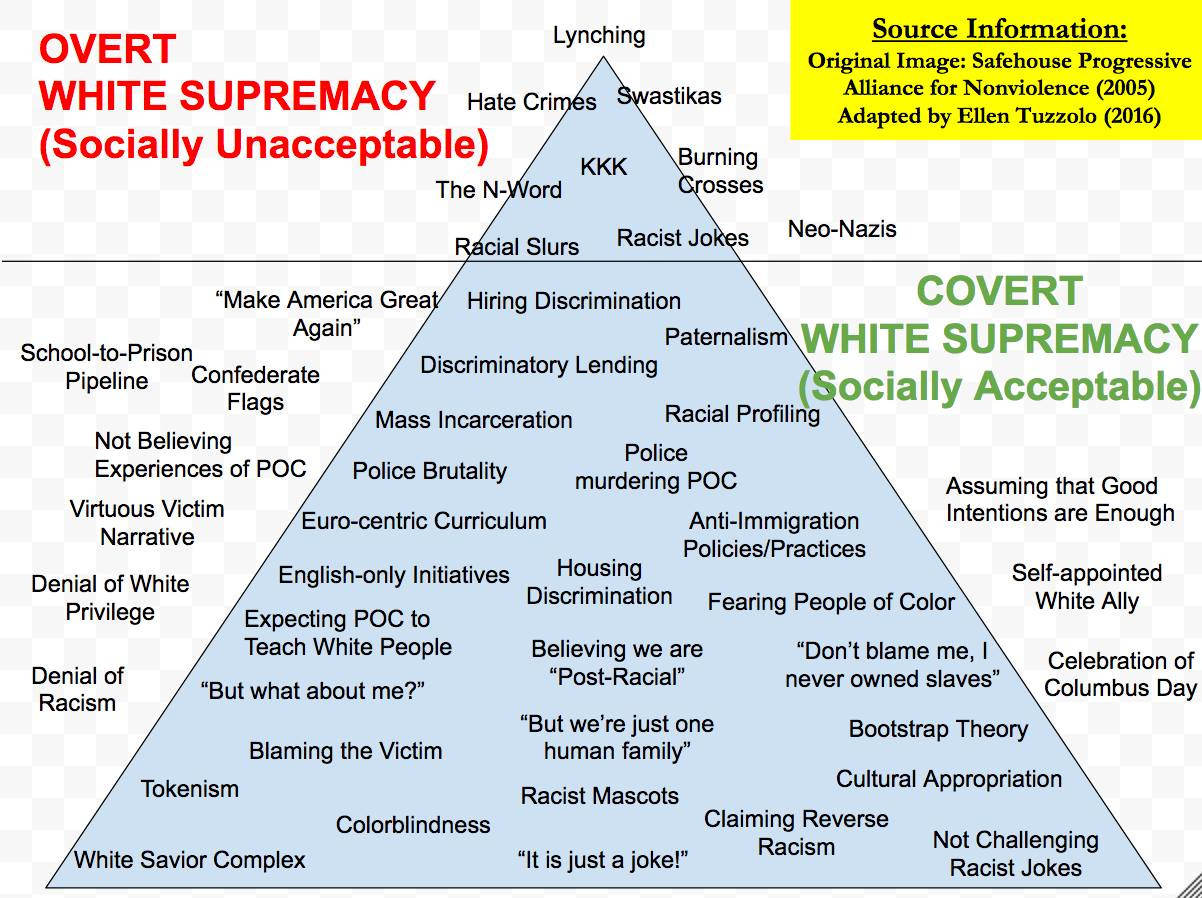

You can also understand white supremacy in pyramid form. At the tip of the triangle are lynching, hate crimes, the n-word, neo-Nazis, the KKK. Just below this tip are colorblindness, white silence, and calling the police on Black people. Toward the bottom is “meritocracy myth,” “cultural appropriation” and many other apparent manifestations of white supremacy. These ideas have been around for a while, but have experienced a revival due to the collision course of Trump and Floyd. If one of the two hadn’t happened, how powerful would this story be right now?

Then there’s critical race theory, a decades-old legal theory that’s made it mainstream. The right has made this their cause du jour, going so far as to introduce bills to thwart its teaching in schools, calling it un-American, and accusing it of foisting guilt upon white children and even infants. The left’s response has been a huge eyeroll: the racist nuts on the right don’t even know what CRT is. They just want to shut down the teaching of America’s history of slavery, racism, and exclusionary acts. Unfortunately, these two sides are screaming past each other. Conservatives may need to calm down and get back to defending free speech, but liberals need to hear where they’re coming from.

CRT is branded as just a way of chipping away at systemic racism. But according to one definition:

The critical race theory movement considers many of the same issues that conventional civil rights and ethnic studies take up, but places them in a broader perspective that includes economics, history, and even feelings and the unconscious. Unlike traditional civil rights, which embraces incrementalism and step by step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and principles of constitutional law. (Emphasis added)

Supporters of critical race theory are encouraged to challenge their opponents to define CRT — as was the recommendation in an ADL webinar — but often when they themselves are asked to defend it, they don’t tack their answer to the definition. Critical race theory is not just about teaching history accurately — something I think we can all agree should be the goal of education. CRT questions traditional, foundational ideals of equality, law, and rationalism. This might indeed be an interesting and even informative lens to apply to the law, in the way that Marxist criticism is an interesting lens for literature but not necessarily fit for widespread application. (But wait: much of the new social justice movement ascribes the cultural and moral failings to capitalism and seeks a socialist answer — and in an ironic twist, companies and individuals who push this narrative are making a lot of money.) I have asked proponents of CRT about this end of the definition, but I’ve never gotten an answer about what it practically means.

All of these documents, charts, lists, and learning tools could be dismissed as obscure tools in an alternate activist universe. In fact, most of the above resources are linked from the Jewish Council of Public Affairs — the national home of the Jewish Community Relations Council — as resources for us to all learn and live by in our Jewish journey to anti-racism.

To be continued…

Community Announcements

Check out the Seattle Jewish community calendar and the virtual calendar.

This week’s parasha is Shoftim.

Candlelighting in Seattle is at 8:05 pm.

Shoutouts!

Shoutout and mazal tov to SBH on the hachnasat sefer torah happening on Sunday. —Elise Hay

I think that you are conflating multiple issues here; I perceive you as saying we should not be trying to be antiracist. As Jews we both have to live with our own experience of discrimination and advocate for others who have been marginalized. Whether that's Muslim Afghan refugees or black Americans, it's part of our tradition to say that we were slaves in Egypt and we will speak out against enslavement and other forms of oppression.

I agree that much of the antiracism work in American is Christian based. As it should be because there was a tie between rationalizing enslavement and the Church. However, there is impactful work being done by the Seattle Federation JCRC and synagogues that is not based on Christian theory.

We have benefitted greatly by the opportunity in America, first to live free from pogroms, and other forms of oppression. We then benefitted from equal opportunity programs as a "model minority" that was less offensive to the Christian majority than black and Indigenous people. By every measure of health and wealth, there is still significant racism in America. I feel compelled to try and fix that because of my Judaism. I would also like to address it in Jewish ways. I appreciate and am learning from the work that URJ, Seattle Federation, ADL, the Holocaust Center and others are doing. If we want to call me "woke", I won't love it, but I'll keep working for equity.

I found your article very disturbing and I'm not sure that I'm even able to call out all the ways that it bothered me. This was just a start.

Linda