The Closure of Mutual Fish Opens a Window into Jewish and Japanese Friendship

Jewish support of the Rainier Avenue fish shop can be traced back to the early 1900s, the Central District, and World War II.

The quiet retirement announcement by Mutual Fish’s Yoshimura family, in the form of a sign taped to the front door of their Rainier Avenue shop, marks more than the closure of a beloved local business. It symbolizes the decline of a long and diverse history of family seafood businesses in Seattle, and it takes with it the memory of a deep relationship between Japanese and Jewish families dating back to before World War II.

“Back in the day, the Jewish community bought fish from the Alhadeffs and the Calvos,” says Joey Alhadeff. From the time the Alhadeffs and Calvos arrived to Seattle from Rhodes and Marmara, Turkey, respectively, in the early 1900s, they established themselves as competitors in the fish business down at the waterfront. Simultaneously, Asian and Greek immigrants opened their own businesses. “When you went into the Japanese fish market, you didn’t hear English, just Japanese,” Alhadeff recalls. “Same with Sephardics: you just heard Ladino.”

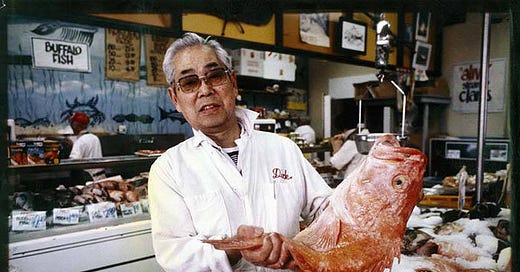

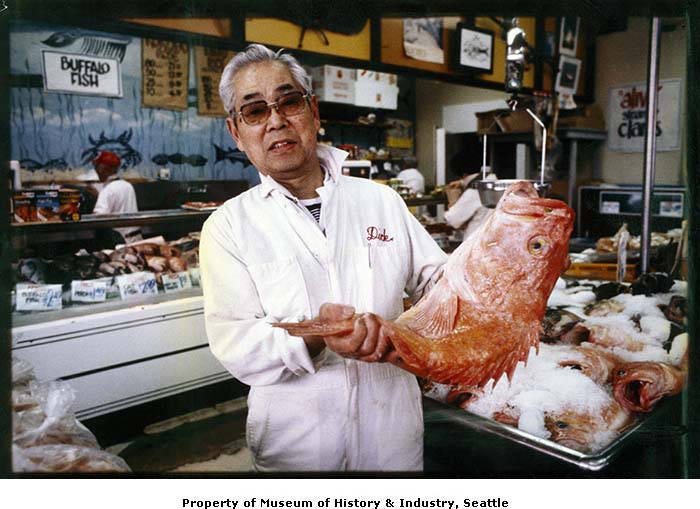

Dick Yoshimura immigrated to Seattle from Japan in 1929 and worked at the waterfront with everyone else, establishing relationships with the other fishmongers. Both the Japanese and Jewish communities settled in the Central District, and all their kids went to Garfield or Franklin High School.

“The seafood business in Seattle, for the Jews and non-Jews, they were all very close,” says Alhadeff. “It was a tight-knit business, they did business with each other, they all had disagreements, but it was very tight. They were all competitors but they all bought and sold and respected [each other]. ‘You’re charging too much, go to hell!’ The next week: ‘Can I buy from you?’”

When World War II came around, however, the Jewish community quietly watched their neighbors and fellow business owners disappear to internment camps. Yoshimura was sent to an internment camp in Idaho, and when he came out, he had to start over.

“It was quite an ordeal, but they survived it, and they had a lot of support from the Jewish community after the war, which helped a lot,” Alhadeff says.

It’s a topic few people are left to talk about first hand; it’s also a topic many of them never wanted to talk about.

Josh Tuininga, a graphic artist who lives in North Bend, recently discovered that his uncle’s grandfather helped his Japanese friends by renting out their houses and paying the mortgage, so they’d have homes to come back to. Tuininga’s uncle is Marco Calvo, one of three Marco Calvos named after the original fishmonger. The discovery led him to oral histories and interviews and ultimately a graphic novel, We Are Not Strangers, which just came out this week.

“It was rare, but there were stories like this where people kept people’s businesses afloat,” Tuininga says.

Other stories like this one are out there, living as oral tradition among an aging population. Out in Walla Walla, for instance, the Barer family held onto land for their interned neighbors. The instances of cooperation were all done quietly. Seattle’s organized Jewish community said virtually nothing about the internment, perhaps out of fear around Japan’s alliance with Germany, or fear for their own security. “Jews had to remain silent, because they needed the US,” Tuininga says.

One Jewish family, who wishes to remain anonymous, hid a Japanese family in the basement of their Central District home during some part of the war.

“My brother just recently told me that as a child there were ‘people’ [in the basement] — he didn’t know how many — after the Japanese were [sent] to the relocation camp,” the family member says. “He remembered that they never went outside and never came upstairs. He remembers my mother bringing a tray of food down every night. He was 4 or 5 years old. He did vividly remember the very stern warning from my parents: don’t you ever say anything to anybody; no one lives in our house but our own family.”

Now in his late 70s, he’s just finding this out. The story makes him choke up. Even 80 years later, the children are holding on to their parents’ secret.

“It has such an interesting analogue to what happened in Poland and Germany,” says Joel Benoliel. Benoliel lived across from the Bergman family, of Bergman’s Luggage. Benoliel recounts that after the war, Fred Bergman sold his house to Japanese friends, the Tokudas, when the banks weren’t friendly toward Japanese borrowers.

“My dad had a luggage store on Jackson, and he had a lot of Japanese friends,” says Fred Bergman’s son, Abe, who is 91. “He was very opposed to the [executive] action and spoke out publicly about how wicked it was to imprison the Japanese.”

Wendy Bensussan’s father, Edward M. Bensussan, was a friend of the Yoshimuras and, as a lawyer, helped them with discrimination suits after the war. When the Japanese community was rejected from forming a Lions club chapter, Bensussan sued the Lions and won. In return, the new all-Japanese chapter made him an honorary member. “He was the only Caucasian member,” she says.

Yoshimura went to work for Main Fish after the war, and in 1947 he opened Mutual Fish in the Central District — at the corner of 14th and Washington, Joel Benoliel says (in contradiction to other sources, which state the shop lived on Yesler Way).

“All of the Jewish community who were in the fish business were very, very friendly with Dicky and his brother,” recalls Benoliel, in reference to Yoshimura. Benoliel worked at White Kosher Foods in the Central District as a teenager in the early 1960s. He remembers being sent to pick up salmon at Mutual to resell in the meat market. White Kosher’s owner, Jack Maimon, knew he could trust the quality.

The relationship between the Yoshimuras and several Sephardic families deepened over the years. Jack Alhadeff remembers when his father, Sam, who owned Broadway Fish, was dying of cancer in the early 1960s, the Yoshimura brothers visited every day. Dick even bought him a TV to pass the time. “All I remember is this friend of his, Dicky,” Jack says. “He came over to the house with a brand new television set with a remote control. I knew he was a fish guy, and my dad was a fish guy, and they all went down to the waterfront in the morning to buy their fish together. When my dad finally passed away, that’s where my mother bought her fish, from Dicky.”

In 1969, Yoshimura moved the shop to Rainier Avenue. Around that time, he hired Ralph Israel and Jack Sadis out of retirement from their own fish shop, City Fish. “They fit right in because they knew the fish business, and they knew the Jewish community, too,” says Joey Alhadeff.

With the Jewish community now mostly out of the Central District, Mutual became the place for the South End’s Jewish community to buy their fish.

Elizabeth Rosen recalls how her mother, Sarah Bush, convinced them to prepare kosher kippered salmon and use a kosher knife. “She shopped at Mutual, and one day, I don’t know how she came up with the idea, she went in there and talked to the manager and said, we have a big Jewish community, how about grinding us some gefilte fish?”

The rest is history.

“Mutual deboned smelts. I don’t think anywhere else did this,” says Joanne Angel. “We used to buy pounds of them and fry them for the holidays. It was a specialty fish house. You asked for it, they did it for you.”

“The announcement of the closing of Mutual Fish on Rainier triggers memories of so many great customer service experiences,” Gigi Yellen-Cohn says. “It’s one more addition to the scrapbook of ‘how it used to be to be an observant Jew in South Seattle.’”

Ironically, the store is closing on Rosh Hashanah, a holiday that Jews celebrate with a fish head that symbolizes a blessing: this coming year, may you be like the head and not the tail. This is the last year they can get their fish heads from Mutual.

Kevin Yoshimura, Dick’s grandson and an owner, understands the significance of closing on the holiday. “A lot of the old fishmongers were Jewish and they were our friends,” he says. “They’ve been partners. My dad played golf with the Alhadeffs all the time.”

Kevin isn’t sure what he’s going to do next, but he knows it’s time for his parents to rest. They’d been thinking about the retirement for a few months and wanted to get it over with before the winter holiday season. They didn’t expect the outpouring of emotion from patrons going back seven decades.

“It’s a sad transition, but it’s certainly understandable,” says Benoliel. “The world of retail has changed so dramatically. Borracchini’s is gone, Oberto’s sausage, all those longtime family-owned businesses along Rainier Avenue are closing.”

The closure takes with it a spirit of community, charity, and diversity that were intrinsic to an earlier place and time.

“Hearing my grandparents talk about how the neighborhoods were, it’s something to get back to,” Tuininga says. “These are isolating times. I think that’s why we romanticize it. We have a need for that in our lives.”

Correction: The original story mistated the relationship of Josh Tuininga and Marco Calvo. Calvo his Tuininga’s uncle, not his grandfather.

In other (Sephardic) news…

My story about Samis’s funding of a Ladino manuscript archive at Hebrew University has been republished at Niv Magazine.

Check out former Seattleite Judy Balint’s story about Seattle’s Sephardic community in the Jerusalem Post!

Community Announcements

Check out the Seattle Jewish community calendar and the virtual calendar.

Shana tova u’metuka!

Candlelighting in Seattle is at 7:03 p.m.

Shoutouts

Kol hakavod to Karen Treiger who works tirelessly for the Jewish community! —Ruthie Voss

Super interesting article, especially for the likes of me who don't know anything about the history of that place.