Winning It Together

Local Jewish day schools went against the grain and opened in person while public schools stayed remote. None to date have become super-spreaders. How did they do it?

Clearly, it was not going to go well.

My kindergartner had been ripped from his nurturing classroom and planted in front of a glitchy computer. He was a mess. I was a mess. “Sorry, rough morning,” I would text to his teachers. His teachers looked strained. Or maybe their screens were just frozen.

It was clear to me pretty soon after the school closures last spring that children were going to be pandemic collateral. I didn’t share this thought for fear of sounding callous. Bodies were being piled into refrigerated trucks in New York. And I was suffering because my child had given up on an activity about snails and was now demanding Disney+? Perspective.

Yet I couldn’t help but be struck by the sudden apparent lack of interest in education by our state and national leaders. Kids were sent home on a quasi-vacation that required visiting with nobody and never leaving the house. Parents (mothers, mostly) were thrust into new roles as educators…and managers and chefs and tech support and therapists and house cleaners, on top of any other job they had.

While I intellectually knew that safety was the priority, no number of positive hashtags could hoist me over the sense of abandonment I felt as a parent of young children. How long could my kids go without in-person interactions with their teachers and friends, without the calming rhythm of the school day? All the more so for children in unstable homes, children with learning challenges, children with mental health struggles already. Why couldn’t this nation of entrepreneurs and billionaires come up with a way to keep kids in school and people safe?

“School is not big business. Yet it’s the heart and soul of our economy, our future, our everything,” says Kerri Stern, Seattle Hebrew Academy’s K-8 principal. “I thought we might have this real shift in education. People would realize teachers are indispensable and so invaluable and [that] schools are so supremely important. And it just went away.”

I trace this deflation to June, when the American Academy of Pediatrics put out a statement urging schools to reopen in the fall for all the obvious reasons schools should be open. Immediately, the Trump administration grafted onto the message. Suddenly, the whole idea seemed controversial. Come August, public-school districts in Washington were rolling out remote plans. I waited for SHA, where my kids attend, to announce remote learning. I looked up such insane ideas as “unschooling” as an alternative. I couldn’t fathom a year of Zoom school.

Then, in late August, SHA announced that it would in fact open in person.

They released a codex of guidelines that included staggered dropoffs and pickups, masks, temperature checks, daily health screenings, more masks, spaced seating, and preparation for inclement weather. White canopies sprouted like mushrooms all over the campus for the first few weeks of outdoor learning. (What would happen when it rained? We’d find out.) They also asked us to informally agree to a pledge that, outside of school, we’d follow state health guidelines. In other words: Don’t ruin this for everyone.

“This looks like it’s going to be a shitshow,” one of my friends texted minutes after the guidelines landed. Surely, we’d all be remote within a couple of weeks, either paying tuition for the failed experiment or pulling our kids out and destabilizing the school’s entire existence.

Everyone has their own risk-benefit analysis constantly running like a background app in an overheated computer. Kids’ mental health, adequate education, and parental sanity and productivity square off against personal health concerns, teachers, grandparents and vulnerable friends, social pressure, and the ever-changing barrage of health restrictions and advisories (are you still wiping down your groceries with Lysol wipes?).

For most parents in the Jewish day school system, getting kids back to in-person school weighted heavily against the risks. “Medical professionals were not thrilled that we all continued to mostly stay open,” says SHA Head of School Rivy Poupko Kletenik. However, she adds, “99 percent of parents were full-on for the reopening.”

All the day schools opened with different plans. Seattle Jewish Community School brought just the youngest kids back; Torah Day School brought back kids through grade 4 first, then 5–8 later in the fall. SHA and Menachem Mendel Seattle Cheder brought all grades (preschool–8th) back at once. The Jewish Day School brought back everyone and tests all students and staff with a weekly self-administered saliva test. All the schools played it safe and have gone remote for periods of time, as a precaution or due to a scare or a related case. However, no cases of Covid, to date, have started and spread at the schools.

“We know a lot more now than in March,” says Stern. “Schools are not super-spreader events.”

Who would have thought?

Certainly not anyone whose entire family has been felled by Norovirus — every year, sometimes more than once.

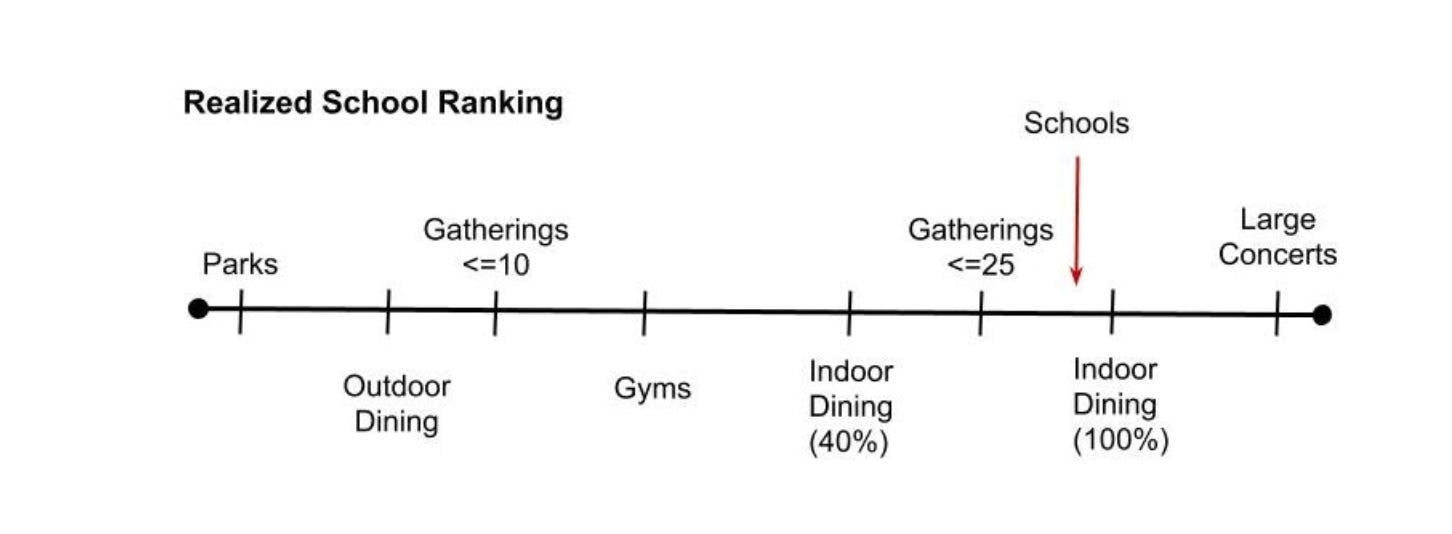

But data from around the country tracks. Emily Oster, over at ParentData, points out that we have been placing elementary and high schools on the risk-factor scale between gatherings of 25+ and indoor dining. But statistically speaking, schools should be placed on the other side of the spectrum, between parks and outdoor dining. Screenshots from the above post (refers to Emily Oster, not me):

Oster, who is an economist at Brown, has written extensively on Covid metrics and how creative solutions could have been employed early to reopen schools. She also helps run a data collection site about Covid rates and safety protocols in schools around the country. Across the board, school transmission rates are extremely low. A parent herself, she advocated for schools (and camps) to reopen late last spring, citing early evidence that schools would likely not become hot zones.

“One might argue, again, that any risk is too great, and that schools must be completely safe before local governments move to reopen them,” she says in a piece for the Atlantic. “But this approach ignores the enormous costs to children from closed schools.”

Some people think it’s luck, or roulette. A teacher at SHA who prefers to remain anonymous expresses skepticism. “I seriously question if we’re going to go back,” she told me during winter break. “It’s bad and it’s supposed to get worse. We’re going to have a post-Christmas surge. People are socializing; 3.8 million people passed through [TSA] checkpoints. That does not mean good things are coming.”

The surge occured. A few local families experienced Covid, but the cases remained isolated. School resumed in January. Had we dodged a bullet? Or have our health and safety protocols proven effective, and can they inform the larger discussion around getting schools back in physical session?

I think the latter is true, but with some caveats.

The day schools have advantages that public schools do not. They are smaller, and some have ample space to spread out. They have the Samis Foundation, which had already souped up their technology infrastructure, making it easy to go remote when needed, and which heavily subsidizes Jewish education here. They did their best to set guidelines for families to follow. And they are not beholden to teachers unions.

“A challenge is teachers. I want our teachers to feel safe. Teachers need to feel safe. That’s not a small thing,” says Kletenik. “When you hear about public schools, a lot of it is teacher pushback. Teachers don’t go into the job thinking their life is as stake.”

The anonymous teacher shared her frustrations about this. “Staff were saying they want to go back, but privately they were afraid. People need their jobs. This is what it came down to, and we have no union to protect us.”

That said, I haven’t heard about any teachers in our schools getting sick or bringing the virus home to vulnerable relatives.

“I try to give my teachers a tremendous amount of appreciation,” says Chaya Elishevits, head of Menachem Mendel Seattle Cheder. According to Elishevits, the teachers were in it with her. Stern echoes this sentiment. Appreciating teachers is much more than putting extra snacks in the break room, Stern expressed to me. It involves a whole new level of understanding, respect for real self-care, and recognition that they are essential workers. “They’re just doers. If there’s an obstacle, they’re going to figure it out,” she says. “Teachers just have this amazing attitude. I would love teachers to be looked at like a real profession. Not patronizing, like, ‘Oh, you’re a teacher.’”

In a way, Jewish history was made for this moment.

“When we look at our history, we’ve been in more dire situations,” says Elishevits. She believes the takeaway is to make the best of difficult situations, and that’s a good lesson to impart on students. Kletenik is also prone to reflecting on the dark moments of Jewish history. “Now we walk out with a mask on. Suddenly this is the new normal….In the ghetto, things got normal for kids, too. But that’s what happens. Humans adapt.”

Let’s be honest. All the day schools are struggling to exist. Staying open and serving their communities is a matter of survival. But it also may be true that religious schools feel a more urgent need to keep the community connected.

“I feel so strongly that given the circumstances, we are safe to continue in-person learning. I don’t want to be over dramatic, but I was raised on Rabbi Akiva and the fish, im ain Torah [if we have no Torah], we have nothing. Yes, there’s Torah on Zoom, but it’s absolutely not the same.”

“I think a lot of it, for the schools, was they recognized the community really wanted them to stay together, stay operating, and try to make it happen,” says Connie Kanter, CEO of the Samis Foundation. “There is the sense of winning it together.”

When I pulled up to school on the first day, I was surprised to see so many families unloading. Through the fall and into the winter, the teachers exuded positivity and happiness, despite the challenges of masking and distancing and the assumed danger of the whole enterprise.

During the second week of school, while classes were still being held outside at SHA, it rained like hell. I stared out the window, wondering how the students and staff were surviving. My son’s teacher texted me a photo of him “fishing” in a torrent of rainwater in the parking lot. Would this break them, send them running back to Zoom school?

“How was school today?” I nervously asked my soaked and freezing children at pickup.

“Great!” They responded. “Best day ever.”

Thoughts? Dissents? Share them in the non-toxic comments or email them to thecholentseattle@gmail.com.

Shoutouts and Announcements*

Mazel Tov to Emily Alhadeff for her efforts in creating a news resource for Seattle’s Jewish community! —Cynthia Flash Hemphill

“Will you still need her, will you still feed her, Connie’s 64.” Happy Birthday, Connie Kanter!

Happy Birthday to Marielle Basseri down in PDX! Carpe Dentum! Seize the teeth! —Etan Basseri

Happy Anniversary to my beloved husband Jon, who reads and listens to more Jewish content than anyone I know. —Naomi Newman

Here’s an idea: If parents and their children plant parsley seeds on or not long after Tu b’Shevat, they should have parsley to be used as carpas for Seder. It will help the young to feel that they have contributed...and they will have contributed. —free advice from Jerry Barrish

Mazels to Wendy Bensussan and Aviva Walls and their families on Aviva being featured on the cover of Washington Jewish Week for being the new head of the Gesher Jewish Day School.

So glad the kids are in school. Agree there are risks, but rewards are far greater. Nicely done article.

Public school teachers are dedicated, but it's not reasonable for them to have the risk their lives and well-being, and that of their family members, for the sake of their jobs. Also, many people live in crowded conditions in multigenerational housing. A family of 5, including an elder, might live in a 2- bedroom apartment. I have known of 2 parents and 3 children (two single moms who were cousins, and their children) living in a 1-bedroom apartment. This is very common, given the escalation of rent prices. The maps on the King County COVID-19 data website show that the incidence of the virus has been very severe in South King County and other areas with more housing density. About 44% of households in King County are renting.